I had set an early alarm, taken a shower, and hooked the already loaded boat to the car late on Saturday night after arriving home from my daughter’s birthday dinner, so there was little to do on Sunday morning but get dressed, leave the perfectly warm and dry house, and gingerly step across the newly laid and very soggy turf in our front yard to the waiting car.

There was plenty of rather wet rain, sock–like early morning overcast darkness and very little traffic, as I drove across the Harbour Bridge, which always seems to be a slightly magical and quite wrong thing to be doing when trailing a boat. For the first time in my life I missed the entrance to the Lane Cove tunnel and found myself on Epping Road, so I took the opportunity to stop at a deserted bus stop and secure something that was flapping in the wind and drizzle before I got to the freeway.

This turned out to take longer than expected due to a crash at Berowra which, according to many warning signs had closed said freeway, so I took the old Pacific Highway past the “Pie in the Sky” cafe (which I had completely forgotten about since the freeway was built), all the way to the north shore of the Hawkesbury River. My main game at this point was trying to pick the right adjective to describe the nature of the rain to my fellow RAIDers (who had driven down from Northern NSW with their boats the day before) when I arrived at the boat ramp, presumably quite late, in a few hours time. I decided on “teeming” over “driven” because the latter seems to have a more horizontal quality to it (discuss). It was certainly spectacular on the old Pacific Highway’s curling descent to the Hawkesbury, where the roadside embankment seemed to be one continuous, dreamlike and quite un-Australian waterfall.

The rain remained either teeming or torrential all the way to the Warnervale services where I donned my Bourke oilskins for the only time on the entire trip (I am sinfully proud of them for their Sydney–to–Hobart chic but I suspect I look a little like a pervert when I wear them with shorts because they’re long enough to cover them completely) and exchanged mumbled “nice day for it”–type pleasantries with a truckie, as I waded across the car park to Maccas. I had intended to go to the F1 cafe because their breakfasts are very satisfying, but there was a queue and I was running late. As I approached Hexham the weather and daylight improved rapidly, with a few hopeful glimpses of blue sky in the far distance, and the boat got a chance to dry out slightly as I made up the remaining distance to Bulahdelah and the Myall Lakes.

The road into the National Park followed the edge of a gum forest on the left and a series of water–logged paddocks bordering the Myall River on the right, all witnessed by the occasional huddle of cows and one or two black faced wallabies. I took the turn to Korsman’s camp ground, crawling along at slow speed behind the last few children left over from the school holidays, until they meandered off the road and shortly thereafter found myself at a launch ramp with two men, one dinghy and glints of sunlight on the water through the trees, about twenty minutes after the designated launch time of nine am.

The dinghy was Don’s, who declined to shake my hand because he was suffering from quite a bad cold. He was having some trouble setting his rig up, because, as it turned out, he had only bought the boat (a Puffin) on Gumtree the day before — sight unseen — and was now trying to marry an old Mirror rig he’d had lying around to it (does this make it a Muffin?). Given the amount of trepidation and planning I had put into getting ready for the trip (it had taken almost a quarter of a century from when I first built the boat for beach camping, to today when I finally got around to doing it), I don’t think I could quite keep the look of shock off my face, but he happily coughed and fiddled away at the boom and sail sagging into his cockpit, so I started rigging my boat.

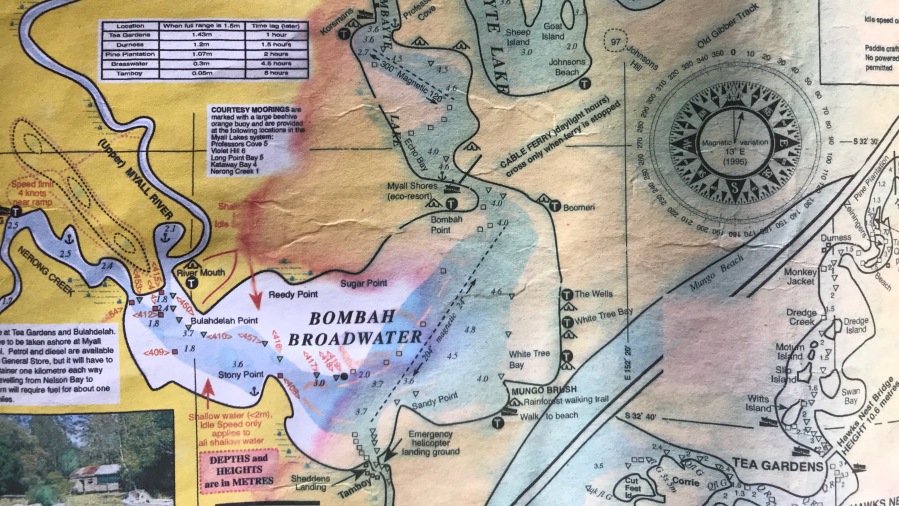

Michael, the instigator of the trip and — quite literally — the man who drew the boating map of the Myall Lakes, had already launched his boat, which I couldn’t quite make out down on the edge of the water. It turned out to be a compact and beamy fibreglass dinghy with a towering mast and white mainsail which I think he said later came out of a land yacht. He was keen to go but was interested in my boat (I think he thought the mizzen was a bit complicated) and, speaking from experience, suggested a few things to check or secure as I set up.

The path down to the ramp had many overhanging she–oak branches, but none low enough to interfere with my masts. The launching ramp was made up of loose, fist sized gravel, and looked over a stretch of river maybe two hundred metres wide, bordered by reed banks. The wind was reasonably fresh and, being a professional coward, I sensibly reefed my mainsail down to its smallest possible size. There was a jetty with an aluminium ladder, sort of nailed onto its front face like a totem pole, which although I don’t think it would have taken any weight, was useful for spotting the launching ramp later on. Don took the painter of the Harry Henry (my boat, details to follow later) and secured it to the end of the jetty, while I drove the car back to the trailer parking spot at the other end of the campsite. When I got back, I managed to transfer to the boat off the jetty without falling in, start the motor and scoot out into the middle of the river, where I set the motor to idle, got my life jacket and EPIRB on, raised the sails, and finally stopped and secured the outboard.

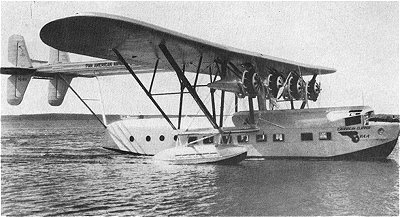

Photo by Michael Smith

Right. After all the faffing about —I’m here. First impressions were that the wind wasn’t too scary at the moment, it wasn’t raining but it looked like a shower was quite possible, and I was very aware that every compartment of the boat (it had many, because beach camping) was crammed full of fuel, water and dry bags stuffed with food, clothes, tents and sleeping gear. At this point at the start of the trip, the pressure to get all this cargo safely to our first campsite weighed heavily on me. I could see Michael’s sail up the passage to windward, while Don was still in the process of launching, so I started sailing up and down trying to keep in sight of both of them. A few minutes later when Don launched, he seemed to be reaching back and forth between the launch ramp and the bay opposite but not coming upwind. I dropped down to see if he was okay, and indeed he was unable to get enough tension in his rig to work to windward. He had an outboard and insisted I go on, but I did hang back until I saw him motoring up towards me.

I hadn’t seen where Michael had got to in the meantime, but I continued to work to windward in the slightly flukey winds in the lee of some taller ground. Eventually I realised that he had pulled up on the opposite bank and that Don had joined him there. I wasn’t in a rush to join them because I thought we were going on, but as it turned out, there was a necessary confab to discuss our upcoming lunch stop at Boolambayte Creek, and I was delaying things. With that sorted out we continued around the corner into the top of Boolambayte Lake, with Don towing Michael under motor and me following in their wake.

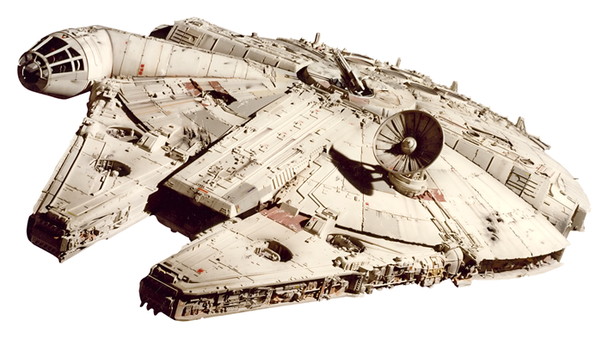

A line of reeds coming out from the north shore marks the entrance to the creek. There are many overhanging branches so I cut my motor and went in behind Don and Michael under oar power. This was quite a fun challenge, as there were snags in the water and branches to get the mast around, and with a combination of quick oar work, craning of the neck and weight shifting to weave the mast Millennium Falcon–like through the overhanging branches, I was able to make it to the site of our lunch halt. I found one of those uniquely Myall Lake–ian mooring spots to pull up, where the bank is held up by tree roots (mainly paper bark in this creek) that act as little slippery jetties next to the boat that, if you’re careful, give you access to the land. The ground was spongy like a modern children’s playground foam, and the trodden paths had knee–high sweeps of dense dark green grass (sassafras?) that curled, wave like, over the path from each side, and took some effort to push through. The lunch site had two concrete tables, and for the first time, I contemplated what to eat, and the logistics of getting food and cooking gear out of the hatches in the boat.

Photo by Michael Smith

The previous week I had taken the forward hatch of the boat — a “glove box” style opening in the bulkhead next to the mast — to the local IGA, so that I could buy some Tupperware to fit through the opening. I got some large boxes that fitted nicely, but at the last moment got some smaller boxes that had more compartments in them as well. I had two drawstring bags, and put one large and two small Tupperware containers in each bag. One bag was sweet, and one was savoury. The annoying thing was that the two smaller containers were slightly too large to fit through the hatch together, so I had to always take one of the small containers out of the bag before I could get it in or out of the hatch. I think I had some Saladas with chilli tuna and some diet soft drink for lunch. Over the course of the trip eating happened more quickly and less memorably than I expected, because every meal was top and tail–ed by a lot of logistics that I generally wanted to be over and done with.

Both Don and Michael had set up burners and made some warm food. Don was preparing his food separately from us to stay gluten free, and I became quite aware of how glutenous my Salada lunch was. A rain shower came through, and at some point we realised that Michael’s boat was now drifting across the creek, which was a surprise given how sheltered it was in there (when reviewing this chapter, Michael gently pointed out that Don tied that knot). I ducked back to my boat and performed a reasonably competent rescue mission under oars, so hopefully some of the earlier delays and trails of glutenous crumbs were forgiven.

Michael was obviously so impressed by this that after lunch he asked me to tow him out of the creek under motor. I tied his painter (quite short) around my boom-kin and tried to get under way, but with no way on the boat I couldn’t steer with my rudder, and, with another boat on a short painter tied to my stern, I found that no amount of turning the outboard could direct either boat. The whole assembly accelerated towards some snags, and before I could snap a mast or break a partner (things which have happened before) I hit the kill switch on the motor, getting away with a mild creak of protest from the partner as the mast contacted some branches and it all came to a stop. Michael agreed that it would be a bit less stressful to get out of the creek without the motor. I think this is also the point that Don, following behind, managed to chew up a bit of the Muffin’s rudder with his propeller, so this probably counts as the high water mark for outboard antics over the course of the trip.

Back out in the fresh winds at the top of Lake Boolambayte we raised sail and set out for Violet Hill. I fell behind while fixing up my tiller extension, which was coming loose, but caught up with the others in the lee of Violet Hill, which cast a huge wind shadow over the eastern parts of the lake. Given how windy it was everywhere else, I think this would be a good place to ride out really bad weather as there is a substantial island that also protects it from the south. We cranked up the motors again with Don towing Michael. I recently added a scarf into my tiller to lengthen it and replaced an old stick I’d picked up to use as a tiller extension (just a few kilometres north at Smiths Lake many years ago) with a carbon–fibre tail–boom from a crashed drone. It’s all actually about 50mm too long now (when I tack I can’t quite fit it behind me and it has to go over my head) but one of the nice things it lets me do is stand up in light conditions or under outboard power, a welcome relief from sitting down for hours at a time. From this standing position it’s a bit ungainly to duck back and adjust the engine speed, so every now and then, when I got a bit close to the rest of the convoy, I’d zig or zag to drop back to a comfortable distance.

We passed trains of ducks, black swans, Violet Hill launch ramp and the camp ground, which despite spending almost all my childhood holidays nearby I’d never visited. We also saw the only other sailboat of the trip at this point, a large fibreglass trailer sailer with a cabin (slight envy) that was motoring in the same direction as us, towards the south end of the big lake.

Not far past Violet Hill the passage sweeps around to the left, bringing the main lake into view. The wind was coming straight down the lake with extreme (20+ knots) prejudice and lines of foam stretching into the distance upwind clearly indicated the wind direction. Michael was raising his sails while Don continued to motor to windward, so I cut the motor and raised the main, still with the deepest available reef and following Michael Storer’s (a boat designer friend and balanced lug rig expert) advice about heavy weather sailing, possibly the most severe application of six–part–purchase downhaul I’ve ever applied to my main. Our first few tacks kept us clear of the shallows on either side of the channel markers and eventually I settled on a long starboard tack across the foot of the lake towards an island which appeared to not be that far away.

There was some chop with a bit of spray coming aboard every now and then, but the boat was scooting along and felt controllable. With his towering and un–reefed rig Michael was pointing higher than I was, and he moved further and further to windward while I continued at slightly higher speed but a lower angle. Gradually the scale of the main lake dawned on me as that tack continued for what must have been about twenty or so minutes. I consulted the boating map that Michael had sent as a PDF which I had printed out, put in a waterproof map wallet and attached to the rudder downhaul line. The Sea to Summit medium case guide map wallet was apparently not at all waterproof, and it was interesting to see how the different coloured inks diffused at different rates through the wet paper. Eventually, when I could make out the individual trees and the shoreline of the island, I went about and started a long port tack towards the distant eastern shore of the lake, with Michael a long way to windward.

In Sydney Harbour where I sail most of the time, I don’t get much of a chance to do long tacks and feel out the boat’s performance, but here I was starting to get a better sense of when I was pinching and losing power. Initially this was as I subconsciously tried to follow Michael’s wake, but once he became a distant triangle of white to windward, it was more when I noticed the power fade and the boat balance become more “sloshy” in the chop. Bearing away, the power came back, I could lean comfortably back into the windward gunwale, with my foot braced against the centreboard case, and slice through the waves with plenty of tiller authority. The handy lines of foam, marking the wind direction like a sea of grid paper in a life–sized instructional sailing diagram, gave me confidence that I was still making good progress to windward, just not at the rate Michael could do with his high aspect ratio rig.

That first tack was as close as I got to the western shore of the main lake, which Michael had warned was shallower and had more rocks. My remaining tacks favoured the eastern shore where there was less fetch for the waves, and where the shoreline wasn’t too distant in order to make out where the Shelly Beach campsite (and presumably Don) was located in the endless line of trees. Looking to windward I can remember the north end of the lake under low, dark grey clouds, which always seemed to be threatening heavy rain that never quite seemed to eventuate. Finally I caught up with the other two boats which were pulled up under some trees on the shoreline. As I closed with the shore, the wind fell away to a calm with clear glassy water over a sandy bottom. I was able to drop the sail and row into another of those amazing Myall Lakes anchorages exactly the size of my boat, between a pair of paperbark trees. Looking back out across the lake to the rain–wrapped hills, there was almost no indication that there was any sort of wind or waves on the water, so consider yourself warned. Looking up between the paperbark trees there was a cleared, tree–bordered grassy area, with a line of deserted camp sites marked out with stumpy wooden posts.

Given that I was a long sail, boat pack up, and short drive away from the nearest motel, my job was now to construct a small house, furnish it with bedding, make a wholesome dinner, and get enough rest through a rainy night to do it all again tomorrow. Michael and Don were already hard at work, stopping only to warn me that they snored (as do I), so I started popping hatches and hauling the various treasures from a shopping spree at Ray’s Outdoors the previous weekend up to the next unoccupied camp site.

My boat has seven separate hatches (because camping) with four of them covering “L” shaped compartments. These compartments can hold one big thing, and a small thing stuffed into the small part of the “L”, because that was the shape of the seats they sit behind. In the forward port side “L” I had my ground sheet stuffed into the small bit, with the tent and camping chair in the main section enclosed in a large dry bag. The ground sheet was a 10×12 foot heavy–duty tarp, which I spread out on the campsite silver side up. The tent was a compact and light two person hiking tent, with an unmemorable name that sounded like a mashup of all the 80s action movie titles I could think of. I hadn’t opened it since its purchase, which was possibly unwise, but if Don could do that with his boat and rig I suppose I could just consider it my own milder attempt to live on the edge. The tent was shaped like a broad, trapezoidal coffin, the inner part being a mosquito net upper and waterproof base, supported by magnetic snap–together pole arches which I found quite impressively 21st century. I would have liked to play with them more but it could start to rain at any point so I attached the arches to the inner and spread the fly out over the top, fussed around, realised it was the wrong way around, and had it all pegged down a few minutes later. I’d brought a heavy hammer from my home workshop for the pegs, but found I could push them easily into the sand by hand.

The forward starboard “L” had an inflatable mattress and pillow in a small dry bag stuffed into the small part of the compartment, and a down sleeping bag in a big dry bag in the main part. No expense had been spared on the mattress, because the main reason I don’t camp is that I can’t get comfortable enough to sleep properly. It had a multi-cell design and a super clever bag that allows you to inflate the mattress in two or three breaths using a venturi effect. It’s so impressive that when the sales guy demonstrated it to me the other customer waiting for him with her son in tow, gasped audibly in amazement. The bean–shaped inflatable pillow took a similar number of breaths to inflate. Another trip to retrieve clothing, a head lamp and books in more dry bags from the boat, setting up the camp chair, and I was ready to weather the night in my impregnable fabric Air Wolf Thunder Dome Tent–a–Tron.

I went through the task of getting the food and cooking equipment out of the forward buoyancy compartment as I had at lunch, only this time it was more annoying. I also brought up one of the two ten–litre water containers from the centre forward hatch. I realised around this point that I did not know where my EPIRB was, and, mentally reviewing the day, realised I did not have it after lunch and may have left it at Boolambayte Creek. Bugger. Michael was already relaxing in a fully set up camp, enjoying some coffee wine that he had made. He kindly offered me some but it was apparently very strong, and I am a cheap drunk, so I declined. Pretty much everything Michael ate on the trip he’d prepared himself, even the beef was from his farm. He has a dehumidifier at home and carried compact, sealable plastic bags of various meals that he could make up by simply adding boiling water. I munched on liquorice and biscuits while I cooked a tin of chilli con carne from IGA on my fuel stove that I had bought as I was building the boat. This was its first camping trip — only two decades later. I also filled the kettle and used one of my all–in–one coffee sachets to make a coffee. The food hit the spot, but as I was washing up without soap, the chilli oil stuck around for the next few uses of the saucepan and cutlery. So if you’re doing wash–up–lite I’d recommend less oily tinned food early in the trip.

Michael mentioned that keeping food in your tent was not a good idea as bush rats, goannas (I knew from my holidays that they could get pretty big up here) and dingoes, had been known to chew through bags and tents to get at food they could smell. I figured that 9mm marine ply would keep them out a while, so I carried all the food back down to the boat, put it in some of the now empty “L” compartments and secured the hatches. It was getting dark and Don announced he was retiring to try and get over his cold. I was also quite tired, from a series of late nights leading up to the trip, so I also announced I was going to bed. Michael reminded me that fourteen hours can be a long time in a tent, but I thought it would be less logistically difficult to transfer to the tent while it wasn’t raining, and I wanted to find out early if there was anything I needed to fix.

The tent fly had large eaves on either side, so I put empty dry bags under the eaves and tucked in the ground sheet around them, so that if it rained torrentially overnight it wouldn’t turn into a kiddie pool with the tent in the middle. The remaining dry bags I kept around me inside the tent. I changed into my pyjamas (quite hard without standing room) and tried to get comfortable, with more success than previous camping trips, but that is a pretty low bar to be starting from. Good as it was, the mattress wasn’t quite thick enough to stop my shoulder digging into the ground. I think my sleeping position didn’t help, because I normally use my knee to stabilise myself and it was confined in the sleeping bag. The mattress also squeaked loudly as it rubbed against the sleeping bag and tent base. Michael showed me, at some point on the trip, a pillowcase that he made for his inflatable mattress that stops this from happening. In retrospect, I think the best scheme for me would have been to take a sheet and wrap the mattress in that, then unzip the sleeping bag and use it as a quilt. Having my pillow from home and not having had a coffee with dinner might also have helped me nod off more quickly.

I had brought paperbacks of Herreshoff’s Compleat Cruiser and the first Peter Grant novel, but couldn’t quite set up the head lamp for comfortable reading. An omnidirectional overhead lamp would have been better for that. Surprisingly, my phone had four bars and plenty of charge, which seemed a bit wrong after voyaging into the wilds, but the illuminated screen was much easier to read in this situation, so I did my usual rounds of the New York Times, ABC News, Financial Review, Washington Post and the Guardian apps. I should have bought something to read on Kindle, or headphones for podcasts (Michael says that he watches movies). At times I’d try to lie still trying not to translate every rustle and noise into a pack of bush rats riding goannas hoping to lick chilli oil off my face. At other times it rained, and, although I could hear wind high in the trees, it didn’t find its way down to the tent with any force. At some point in the night the wet fly over my head came into contact with the top of the inner tent and stuck to it, although no water seemed to make it any further than that.

Thanks to Mark Walker for some much–needed copy editing. Continue reading with Day Two.