I think my main feeling on waking up for the second time, in a tent I had carried to a camp site by sailing boat, through sometimes adverse conditions, was relief. This was firstly due to the fact that I had certainly slept better than I had on the first night, that this in turn meant I would be safe to drive back to Sydney later that day, and finally that the plan was to drive back to Sydney later that day. Don’t get me wrong — this was not an outright recoiling from the dinghy cruising lifestyle, but a prudent response to the prospect of even worse weather, and the rapidly diminishing number of undamaged fingers I could use to pack up camp, sail boats and drive cars with.

The tent, ground sheet and dry bag setup had made it through the wet night with flying colours, and my plan of weighing down the camp chair with the water container so that it didn’t blow away seemed to have worked, as the chair was still there. I have failed to mention up to this point that I had bought two quick–drying camping towels at Ray’s Outdoors, with the idea that one would be dry–ish, and the other wet. Through poor towel logistics, I had managed to leave each of them on the camp chair during a period of rain, so they were now both sopping wet. I spread them and the tent fly on some nearby low bushes to try and dry them out, as I knew they would not be aired until I was back in Sydney. I repeated the previous day’s porridge and fruit salad breakfast, and made a coffee that I forgot to drink until it was quite cool. I remember wondering if I really needed a kettle as well as a folding–handle saucepan. If I boiled water in the saucepan and poured it into the mug with the coffee powder in it, I could then add oats to the remaining water, and have one less thing to manoeuvre into the forward hatch with my long suffering fingers. I can see the attraction of a kettle afloat, with reduced chances of a lap full of boiling water being delivered all at once by a tipping saucepan, but on land it might work.

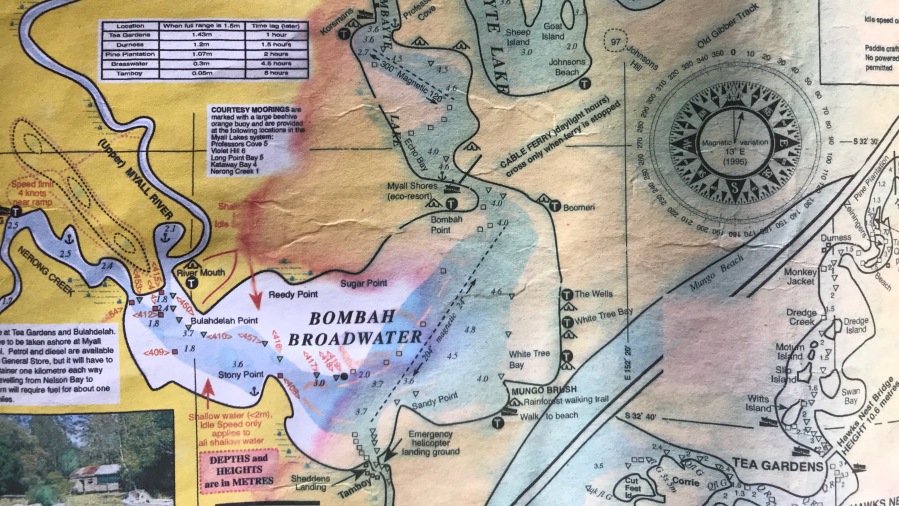

Michael and Don had decided that they were also going home today, but not before a Shackleton’s furthest south–style expedition to Mungo Brush, on the southern shores of the Bombah Broadwater (best said in a Sean Connery voice), the last expanse of water before the Myall River, which drains the whole lake system to Port Stephens, and the Tasman Sea beyond. This would involve a glorious broad reach all the way there, and a more difficult return, but it seemed the natural and right thing to do. Having been thwarted in our attempt to reach the northern extent of the lakes at Neranie the previous day, like gas molecules bouncing around in Boyle’s box, it was our sworn duty as sailing explorers to poke into the furthest extents of our sailing grounds, lest we break the laws of thermodynamics.

Michael was rightly concerned that our launch ramp at Korsman’s was a lee shore in today’s conditions, and sketched a plan in which we would arrive at the ramp at half hour intervals, so that there would not be a pile of boats being blown onto the shore and each other, tangling their rigging in the overhanging tree branches while we raced to get our trailers. At the same time it was acknowledged that I was going to head back, at whatever time I felt I needed to meet my schedule. I called my wife to let her know I was coming back today, and was quickly tasked with taking my youngest daughter to evening netball. Planning backwards from that constraint, I decided I needed to get the boat onto the trailer at around one in the afternoon.

I was slow to pack up camp that morning, partly because I was hoping the fly and towels might dry out a bit more before I packed them, partly because everything I did hurt my hands, and partly due to a last minute nature break at the facility–free campground. This time I was the one still on the shore as the others headed out into the lake and picked up the wind. Knowing that I did not have to camp again that night, a certain weight lifted from me as I considered the ground I would have to make up to catch them. For our last sail together, perhaps I should let them see Harry in full fettle with a glorious un–reefed mainsail? In retrospect it is obvious that I had not placed my tent far enough away from Don’s, and that over the previous two days I had been incubating some virus I had picked up from him. Luckily I had this season’s flu vaccine, which is probably the only thing that stopped me setting the tent fly and towels as stunsails on the ends of my yards, but, as it was, this micro–DON sailor would measure the last morning of his odyssey if not in DONS, then at least in milli–DONs.

While still on the beach I shook out my reefs, glad for my finger’s sake that I had chosen a larger and softer braided line for my pennants. My slab reefing setup hasn’t quite been perfected, the reefing line is not long enough to leave the hooks in the top reef cringles when the sail is full, and needed some coaxing through the blocks on the boom to release its grip on the sail. I swung on the halyard and raised the freed sail as high as it would go, going easy on the downhaul, because I could see from the other boats that the first course across Two Mile lake to Myall Shores and the car ferry was a very broad reach. Pushing off, once again the first hundred or so metres of water marked the change from almost calm conditions at the shore, to a fresh breeze out on the lake, which was enough with my restored sail area and longer hull to start closing the distance with the others. After two days of sailing fully reefed, it was all a bit of an anticlimax, an easy sail between a tree–lined bay to port and well marked shallows to starboard, with the sun shining on the water through a gap in the clouds.

When I caught up with the others just west of the car ferry, their sails were lowered, Michael rowing towards the car ferry crossing, and Don following at a distance under motor. I wasn’t quite sure what the plan was, so I followed Don past the car ferry at rest on the western bank, and around to a sheltered beach on the northeastern shore of the Bombah Broadwater, where he had pulled up onto the sand. I lowered my sail and followed him into the shallows within speaking range, but he said he was continuing on. I then noticed that Michael was under sail again, and well on his way out into the Broadwater. I raised my sail, adding a little more downhaul tension as I considered the wide expanse of water to the south, and spilled wind waiting for Don to to join me. The protective shore fell away to the north and we took up an echelon formation maybe ten to twenty metres apart, where we could admire the other boat, when we weren’t otherwise occupied with the effects of the increasing wind and waves. The Muffin was coping well with the conditions, and for a racing dinghy seemed to be keeping Don reasonably dry. The red mirror jib and gunter main were so full they looked like a parachute behind a drag car, and despite my waterline length and sail area we seemed evenly matched for speed. I took a few good looks back at the shore and the hills behind to memorise the position of the passage to Two Mile lake before it merged into the rest of the shoreline.

The conditions were not dissimilar to the previous day’s, but the speed of the broad reach and perhaps the reassuring proximity of the other boat seemed to make this journey across the Broadwater less fraught and more exhilarating, despite my lack of reefs. The lee rail was still near the waterline but with the speed comes a deep hull–length wave that overwhelms any smaller waves that would try to take advantage of the reduced freeboard to slosh aboard. About half–way across Don had tried shouting something to me, and having no idea what he was saying I nodded, smiled and did all the other things you do to be polite in such a situation. I was dealing with an increasing amount of weather helm in the large gusts that rolled across the lake, less sudden in their onset but relentless once present, more cannon balls than bullets. What Don had been trying to tell me became apparent in one of these a minute or so later when the weather helm became irresistible and the boat headed up so quickly that the centrifugal force had me doubled forward over the centreboard case waiting for the boat to trip over its lee gunwale and swamp, as had happened on several other boats in my younger days.

By the way, the Harry Henry has never capsized. The closest it ever came to disaster was again on Smith’s Lake nearby to the north, when I was sailing with a friend who professed sailing experience and wanted to tend the mainsheet. Shortly thereafter we were caught beam on in a squall (for a small body of water, Smith’s Lake has more than its fair share of weird weather). I remember the boat blowing sideways under a full press of canvas scooping up water like the bucket of a bulldozer, with him on his back on the lee gunwale using the mainsheet to hold himself up, and me screaming “Let it go!” repeatedly like a death–metal Queen Elsa. As soon as he did, the boat popped straight up. With that important addition to his sailing experience my friend returned the mainsheet to me without complaint and got busy bailing a considerable amount of water out of the bilge. I’ve meant to set up a practice capsize in sheltered waters several times over the years, but I’ve never got around to it.

In this case, the Ness Boat came to a stop head to (blasting) wind in the choppy waters, and I quickly realised that Don had been trying to tell me that the rudder had floated up (I have been meaning to do something about my rudder downhaul line/cleat combination for years) causing my weather helm. With a quick pull on the downhaul and a glare at the cleat, I bore away onto our original course, assisted by briefly back–winding the mainsail with some hand pressure on the end of the boom. Eventually the shoreline to port closed with our course, and we could see Michael’s boat pulled up on a beach, with a very established looking campsite complete with motorhomes and paved roads behind it. As before in these lakes, the water conditions magically dialled back towards calm winds and flat glassy clear water as we approached, even though this was not a weather shore. I nosed into the beach and assayed the Mungo Brush camp ground. The vegetation at the north end of the beach was quite different to the trip so far, with a dense rainforest canopy including palm trees. Michael pointed out a dingo with bright orange hair trotting like a boss across a nearby lawn, and a couple from the campsite came down to the beach to admire our boats.

This was a morning tea stop for Michael and Don, but aware of the time I knew I had to turn around, and head back to Korsman’s if I wanted to keep to my schedule. Rooting around in the narrow part of my starboard aft “L” compartment, I found my supply of “R” signal flags that I bought as gifts for the skippers of boats who join me on RAID–like activities, and presented one each to Michael and Don, with thanks for the invitation and their company. Handily “R” is the only letter in the International Code of Signals that has no meaning when used on its own. I propose we fix that and assign the Kenneth Grahame–esque meaning “I am Messing About in a Boat — Remain Clear” so that we can recognise each–other on the world’s waterways.

Thinking of the conditions I had just experienced on the Broadwater, and that this would be a windward leg, I prepared for Gentleman Mode, and in a moment of gallows humour suggested to Michael that when they traced my path later that day, they keep an eye out for an overturned blue hull. Pushing off I cranked up the Tohatsu, waved farewell to Michael, Don and the camping couple, and pointed my stem at the peaks I had memorised to mark the passage to Two Mile Lake (checking just now on Google Earth, these are on the northeast shore of Boolambayte Lake above the road to Violet Hill). The conditions rapidly deteriorated. This time I was travelling into the teeth of the wind, which itself was less of a concern with my mainsail lashed on the floorboards, but the short high chop that built up with (checks Google Earth again) less than three kilometres of fetch was ridiculous. In the Broadwater proper every fifth wave or so would pitch the Tohatsu up out of the water causing the motor to race and the boat to slow down, accompanied with a flying lap–full of spray. If it got any worse I worried that it might take so long to cross the Broadwater that I’d run out of fuel and I’d need to run away to the western shore under sail, because I would have great difficulty leaning out to refuel the motor in the rapidly pitching boat, and rowing would be futile. After a few minutes of this, I shifted my seating position from the little motorbike seat on the rear of the centreboard case, to the rear buoyancy tanks to sink the propeller a few centimetres lower in the water. This seemed to solve both the motor and the spray problem, although the front of the boat was spending so much time in the air I suspected it would look like one continuous wheelie from the shore. For a longer term solution I should really adjust the shape of the outboard bracket, which was designed for the British Seagull and should be a little smaller and lower for the current motor.

Slowly I closed with the marker posts leading to the passage, and details of the northern shore became distinct. The chop faded away although the wind remained, and even allowing for relative motion was certainly much stronger than it had been when we passed through earlier. I rounded the last marker into the narrow channel, and crossed the ferry which again was stationary on the west bank — my epic crossing of the Bombah Broadwater having taken about half an hour. I exchanged a friendly wave with a fisherman on the eastern shore, and checked my fuel level through the transparent side of the exposed fuel tank. I had painted the fuel tank black, and masked a strip on the boat side of the tank so that I could see the level, but as it turned out the paint was not fuel–proof, and had started to slough off the tank anyway, making my masking unnecessary. I had expected to almost be out of fuel, and was surprised to see about two thirds remaining, so I continued, rounding a reedy promontory (reeds!) for a final dash along the channel markers of Two Mile Lake. It was windy but the chop was small. Nearing the previous night’s campsite, I turned westward towards Korsman’s, the engine picking up speed as the mizzen enjoyed a last beam reach and helped to push me on towards the stretch of water we had started on two days earlier.

Approaching the ramp my thoughts turned towards recovering the boat onto the trailer, and Michael’s concerns from the morning. I have a healthy respect for the perils of a lee shore — a year previously I had held the Ness Boat bucking in a two metre surf at Abrahams’ Bosom beach on the South Coast, arranging a crew to help get it back on a trailer. On another occasion I had sat through my sister’s birthday lunch at Doyle’s in sopping wet casual clothes, with my daughters in hysterics because my dear mother had insisted that my family arrive in Harry Henry, (some much loved Henry cousins were attending from interstate) and with a big swell running into Watson’s Bay that day, my only option was to drop everyone on the beach, anchor off and swim ashore.

With all this in mind, I motored up to a guest mooring in the shelter of Professor’s cove opposite the ramp, shut down the engine and proceeded to unship the masts, which is a reasonably straight forward thing to do in a boat with no standing rigging. The boat gets a little more twitchy with the mast down, and stepping around it once it’s in the boat takes a bit of Twister–like planning, but five minutes later I was able to unmoor and sedately motor over to the ramp, where I cut the outboard and glided into a tiny cove under the she–oaks, a few metres to the south of the ramp. I walked through the now deserted campsite to the trailer parking area, and was relieved to find the car and trailer there. Settling into the driver’s seat with arrays of technological bling in front of me was surprisingly surreal, and I mused on why this was so on my way back to the ramp. Getting the boat back on to the trailer I discovered that between the cove and the ramp there is an area of very soft mud just before the rocks that make up the ramp, so consider yourself warned. Packing up the boat was slow with my damaged fingers. I had huge quantities of fresh water left over in my containers, so after removing the bung from the boat I rinsed the sails and interior with their contents. I threw all my dry bags in the back of the Forester, secured everything that moved, and piled a supply of snacks on the passenger seat. Eventually it was done, so I took a moment to take in the wind rushing through the leaves overhead, the stretch of water at the end of the ramp, put on my 21st century face and got into the car.

When I got back to Bulahdelah, I was not quite ready for the Pacific Highway, so I took a turn down the hill to the Myall River to check out the houseboat hire business, another place I had spent my entire life going past, but never visiting. To reassure myself that this wasn’t an immediate betrayal of the sailing–camping ethos, I told myself that this would only be used as a support vessel for a future RAID mission, an idea that had briefly been discussed with Michael and Don. I arrived at the same time as a suburban couple, and soon afterwards the crusty master mariner owner of the business introduced himself, and offered a tour of the boats. They were nice boats as houseboats go, (I do wish you could still hire cabin sail boats on the lakes) but my main concern was how they would go in the sorts of conditions I had just experienced. This line of questioning encouraged the master mariner, who started talking about the draft suitable for the Myall Lakes (0.5m), the thickness of the fibreglass hull (50mm), the unbelievably stupid things some of the hirers had done, (ask me at the pub) and the apocalyptic survival conditions he had sailed the houseboats through on an improbable number of occasions. I would like to apologise to that couple, who probably started as potential hirers, but I think were increasingly appalled, and I would not be surprised if their holiday plans changed to an extended stay at Lightning Ridge, or some other location a long way from any large bodies of water. After that I drove back to Sydney with a stop for fuel and the F1 cafe at Warnervale services, Sydney traffic, and a windy but entertaining night netball game, which my daughter’s team won convincingly. I got a text message from Michael saying they had made the ramp at around five in the afternoon. They had started beating across the Broadwater, but so much water was coming aboard that they swapped to motors. The following day was spent drying and airing, doing a wash, and revising my dream boat plans from my home office sofa.

One day there will be a shallow draft trailerable motor sailer, with a cozy Halvorsen–like back deck for reading books in an anchorage with my wife, (that’s her sort of sailing) but, in the meantime, I have finished Roger Barnes’ book, (excellent and somewhat less terrifying than Margaret Dye’s) and have a list of improvements to try on Harry. Following the example of Michael and Don, I’ve been wondering just how much of a boat you really need to do this, as something that didn’t need a launching ramp would be a great relief around Sydney, where ramp rage is a leading cause of sailing stress. For the purposes of further experiment, I have a few of Michael Storer’s smaller boat plans, Iain Oughtred’s Auk plans and a pile of Gaboon plywood in the workshop.

This time, I won’t wait almost a quarter of a century to take whatever comes out of the workshop camping. As Michael said in his galvanising Facebook invitation for the trip: “Go small, go simple, go now”. I did.